Showcase was probably the most important DC magazine of the late 1950s and early 1960s. It was intended to showcase new comic characters to see if teenage boys would buy them before launching a new book.

The first three issues featured Firefighters, Kings of the Wild, and Frogmen. Apparently none of them struck a chord with the public but the fourth issue hit the jackpot:

The Flash had been a Golden Age character, but this was the new Flash. Where Jay Garrick had been a research scientist with his own laboratory, Barry Allen was a police scientist. Barry wore a face-covering mask, while Jay had simply worn a helmet and vibrated a bit so his features were blurred.

After Showcase #5, featuring Manhunters, Showcase went on a remarkable run. Starting with #6's Challengers of the Unknown, every feature published in Showcase up until #40 graduated to either its own magazine or (in the cases of Adam Strange and Space Ranger), became cover features in other DC magazines. In rapid order, the DC cover stars of the 1960s appeared: Flash, Challengers of the Unknown, Lois Lane, Space Ranger, Adam Strange, Rip Hunter Time Master, Green Lantern, Sea Devils, Aquaman, Atom and Metal Men. Flash lasted for 246 issues, Challengers for about 80, Lois Lane for about 130, Rip Hunter for 30, Green Lantern for 90, Sea Devils 35, Aquaman 56, Atom 45 and Metal Men 45.

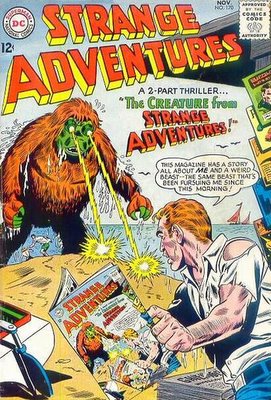

After that, either DC's ideas began to run out, or Marvel began cutting into the sales, or (my opinion), DC stopped trying to create new superhero titles. From 41-54, none of the features were deemed worthy of continuing. Tommy Tomorrow (a DC sci-fi hero since the 1940s) was given the big treatment in 41, 42, 44, 46 and 47. Issue #43 was a one-shot Dr No (had DC gotten rights to the movie without real rights to James Bond?). #45 featured Sergeant Rock, who of course was already a cover feature in Our Army at War. Issues #48, 49 and 52 featured Cave Carson, a spelunker who mostly battled weird monsters inside earth and who had already a pair of tryout trilogies in Brave & Bold.

And even when it went back to featuring superhero debuts, Showcase did not get its mojo back. Aside from the Teen Titans (who had effectively debuted in Brave & Bold although they were not called that), and the Phantom Stranger, none of the characters featured in the rest of the run of Showcase lasted for more than ten issues of their own mag, and most didn't even manage to get off the launchpad. Consider these features: B'wana Beast, the Maniaks, Johnny Double, The Creeper, Anthro, Hawk & Dove, Bat Lash, Angel & Ape, Dolphin, Firehair, Jason's Quest, Manhunter 2070