With the upcoming Watchmen movie, I thought it might be a good time to look back at the Question, the inspiration for Rorschach in the movie. Charlton Comics had been around for most of the Silver Age, churning out a mostly low-budget line of war and romance comics that apparently sold well enough to continue publication. At times they had brought along some terrific talent, like Steve Ditko, who did some fine science fiction for them in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Ditko went on to co-create Spiderman and Dr Strange, and was one of the major talents at Marvel in the early years. But he apparently never burned his bridges behind at Charlton, and so he made a quick landing after abruptly leaving Marvel after Spiderman #38.

Ditko also brought instant credibility to an effort that Charlton needed in superhero books. Like many other publishers, they experienced a surge in interest for superheroes. But unlike Harvey or Dell which jumped in with obviously inferior products, Charlton, under Ditko's guidance, actually produced some memorable books and characters.

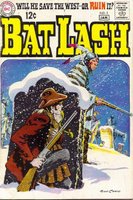

Charlton reprinted a few stories that Ditko had done in the early 1960s featuring Captain Atom, with a backup revival of the Blue Beetle, a character from the very early Golden Age of Comics that Charlton had already tried to resurrect several times in the 1960s. In June of 1967 Charlton gave the Beetle his own title for the third time that decade, and for a backup feature there, they published the Question. Note: According to the Grand Comics Database, while the credits for the stories listed the Scripter as DC Glanzman, in fact the stories were written, plotted and drawn by Ditko.

Who is the Question? Steve didn't leave us in doubt long with a dramatis personae to lead off the first story:

Vic Sage plays Steve Ditko's idea of what a hero should be. Ditko was a disciple of Ayn Rand, a writer who formulated the political philosophy called objectivism. The subject of objectivism is beyond the scope of a post on Silver Age Comics, but suffice to say that the objectivists believed in rugged, uncompromising individualism, and Sage represents this philosophy come to life just as much as Howard Roark, the hero of Rand's The Fountainhead

The first story begins with a raid on a gambling joint. One of the gamblers is a three-time loser, so he shoots a cop in order to escape. Sage reports the manhunt for Lou Dicer, but then indulges himself in a little editorializing:

This establishes a pattern for the series; people are always griping about Vic Sage, but the savvy old man running the station refuses to fire him. Why? Well, maybe it's because he gets people standing around on street corners watching his newscasts.

After the show is over, Sage decides to capture Dicer, and reveals to us the basics of how his double identity of the Question works:

Dicer has an accomplice and the Question tails them and informs the police of the impending meeting of the two. It turns out that the accomplice is an employee of WWB, the station that Sage works for. This will be terribly embarrassing for the station if Vic broadcasts it, but:

In the next issue, a young circus apprentice steals a trick cape that enables one to fly using air currents and helium, and becomes the Banshee. In an interesting twist to what was still common in the Silver Age, the hero does not flinch from combat even when he's in his normal identity:

But some bleeding-heart weenies intervene:

Ditko twists the story here to make more political points. Is it really believable that folks who shied away from the Banshee when he tried to rob them would suddenly intervene to help him when he was still not subdued? But you see what Ditko is doing. The others in the room are liberals who want to coddle criminals while Vic is Dirty Harry.

The Banshee gets away, but the Question keeps alert for the next week and eventually they have a battle. As it happens, the Banshee's costume betrays him:

A fitting end for his kind, anyone?

There are more than a few similarities between the Question and a character Ditko would develop for DC a year later called the Creeper. Both had alter egos who were broadcasters, both transformed into their crime-fighting duds in a mist, and in the third issue, the Question laughed maniacally, a signature of the Creeper:

In the fourth issue we get more of Sage against liberals:

There are several subplots going on. As you can see, several of the people at the station are plotting Sage's downfall. He's dating the blonde (Nora), but the owner's daughter also has her eye on him, although he pointedly ignores her interest. And we can see that he's got himself one courageous and upright gal in this sequence:

She even contributes to her and Vic's escape. Later in the story, we see one very marked difference between the Question and any other hero of the time:

Again, Ditko is using the moment as a lesson in the harsh realities of objectivism, which holds that nobody has an obligation to help anybody else. Ditko makes it fairly easy for us in this instance. We have, after all, seen one of the men hit a girl, and the other was quite prepared to shoot her, and any rescue attempt would be risky for the Question. But a true objectivist would argue that the Question similarly has no obligation to rescue a drowning baby even if there were no risk to himself (although of course he could heroically decide to do it of his own volition).

In the fifth issue, Vic crosses over into the Blue Beetle story, and Ditko lets us know his opinion of pop art:

There was a somewhat similar display of "art" in Amazing Spiderman #22.

Vic doesn't think much of hippies:

Of course, he was swimming very much against the tide on that score in 1967. In this issue, the Blue Beetle and the Question stories both feature that Ebar, the art critic, who is clearly based on the character Ellsworth Toohey character in The Fountainhead. Ebar explains his philosophy here:

Ditko is weaving in a discussion of his philosophy about superheroes as well as heroes. Is he also getting in a sly dig at Stan Lee, who was a well-known proponent of flawed heroes?

In the Question story in this issue, Vic buys a painting for Nora, which Ebar sees. It bothers him that the picture features a heroic pose, and the memory of the picture eats away at him:

Of course, the obsession to destroy a hero was a major motivation for another famed Ditko character: J. Jonah Jameson.

Ebar hires some crooks to destroy the painting, giving the Question an opportunity to smash up a couple of thugs. Realizing that Ebar was behind the attempted destruction, the Question deliberately toys with his mind:

And eventually the art critic makes an attempt to destroy the painting himself, which results in his capture and arrest.

Unfortunately, that was it for the Blue Beetle series. The Question did make one more appearance in the Silver Age (more on that later), but I did want to close this post by talking a bit about the differences and similarities between Rorschach (as characterized in the original Watchmen series) and the Question as characterized by Ditko.

Similarities are obvious: The coverall face mask, the absolute conviction in the righteousness of his cause, fearlessness, great fighting ability and quick wits. Both have a slightly sadistic streak but always directed towards those who have already shown they deserve nothing better.

Differences: Vic Sage is obviously nothing like Walter Kovacs, the alter ego of Rorschach. Sage is handsome, worldly and speaks his mind, while Kovacs is homely, introverted and guarded. And the Question is more prone to explain his actions in terms of his philosophy. While Rorschach has a moral code, he doesn't explain it, he lives it.

Coming Up: A Single Issue Review of Mysterious Suspense #1, the final appearance of the Question in the Silver Age.